In the manner of so many of our most influential creatives and thinkers, the person of Jim Henson—creator of the Muppets, voice of Kermit the Frog himself—remains present in our collective imagination as an enigmatic figure rather than as a man. The time since his death over thirty years ago has only served to solidify this image further. Ron Howard’s documentary, Jim Henson Idea Man, is an entertaining, loving, and at times very moving portrait of the puppeteer as an artist. Biographical works on the deceased often feel somewhat spooky in this way: the subject can no longer contribute anything new to the conversation on his life and work beyond what has already been said, done, and interpreted by those around him. His voice on the matter is a limited one. There remains something inaccessible to us about the man himself, so we must settle for getting to know the artist through the legacies he left behind—his friends, his children, his work, and the beloved collection of fine-feathered and felty characters who continue to delight generations of children and adults alike.

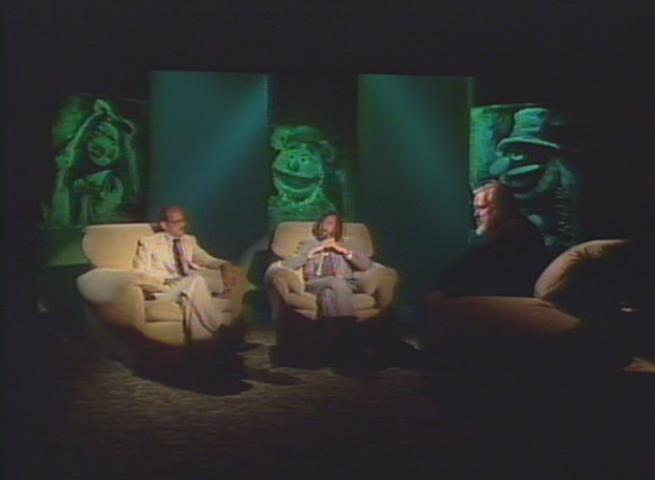

Idea Man traces the history of the Muppets from their conception in the 1950s to the creation of Sesame Street, through Henson’s struggle to get The Muppet Show on the air, to later forays into film and television like The Dark Crystal, Labyrinth and Fraggle Rock—all of which met with varying degrees of success. Highlights include interview footage of Henson and Frank Oz (alongside Fozzie Bear and Kermit) from the unaired The Orson Welles Show pilot; clips from a 1965 (Oscar-nominated) short film, “Time Piece,” which served as the basis for early Sesame Street segments; and selections from the public access television Muppet days, including an early iteration scandalously titled The Muppet Show: Sex and Violence. New interviews with the likes of Henson’s children and Frank Oz round out the film and strive to shed light not only upon the man himself but also upon the lasting impact of his work.

A later segment of the film details Henson’s struggle to find a new home for the Muppets in the late 1980s. Their eventual acquisition by the Walt Disney Company contains some shades of a deal with the devil: helping to secure the Muppets’ future, but at the price of damning the iconic puppets to an endless cycle of reboots and reimaginings that might ultimately diminish their reputation in the eyes of future generations. At the very least, it has kept The Muppets in the conversation regarding children’s entertainment. The Disney-produced doc sidesteps the complications that abounded from this acquisition and instead frames the Disney move as an act of love on Henson’s part, intended to preserve the rights to the Muppets for his own children and to maintain some semblance of creative control over the Jim Henson Company properties. In this way, Idea Man highlights Henson’s passion for his work as something deeply personal—in spite of the large amounts of money at stake—and his desire to maintain a strong legacy for his children as prominent on his mind.

A man of profound imagination and talent, Henson’s story is complicated by his relationship to his family, and in particular to Jane Henson, his wife and early creative collaborator. Jane’s presence in the film is felt mainly through the fond memories shared by her children, due to her passing in 2013. One walks away with the sense that Henson’s inability to let go of his somewhat conservative family values ultimately prevented the possibility of maintaining a more balanced and creatively fruitful partnership with his wife. What started as a 60/40 division of power in the company dwindled as children came into the picture, and Jim seemingly saw his wife’s role as reduced to that of a homemaker. Anecdotes suggest that her attempts to join the conversation regarding the business side of The Muppets were largely shut down by her husband, much to her displeasure—a conflict which eventually contributed to the dissolution of their marriage.

Howard spends a portion of the documentary exploring Henson’s relationship with death—particularly, the impact of losing his older brother at a young age. The discussion of his grief over this loss so early in the film serves as a way of foreshadowing the subject of Henson’s own passing at age 53—a subject which inevitably dangles like a sword over the head of any audience member with even a basic knowledge of Jim Henson’s life.

The film glosses over some of the specifics of Henson’s death—a result of toxic shock syndrome and seemingly a side effect of Henson’s characteristically intense work schedule and refusal to rest or seek medical treatment when he became ill. And though the documentary does not draw a direct connection, Henson’s upbringing in the church of Christian Science—a detail mentioned in reference to his lack of religious affiliation later in life—feels especially relevant within the context of his death. It seems unfair to speculate, and perhaps in poor taste to place too much blame for such a loss upon any one person or entity, but Howard’s film avoids this discussion altogether. It instead focuses upon the shock and sorrow of his children—and mainly, their desire to fulfill their father’s wishes for a bright, upbeat memorial service.

Footage from Henson’s funeral reveals the unique specifications made by the puppeteer prior to his death—and anyone who’s watched this footage can understand it as a simultaneously joyous and cathartically devastating event. It showcased performances by Muppeteers, loving tributes from friends and family, and the insistence that no one wear black. In the context of a memorial service, even the silliest and most lighthearted of moments feels devastating and bittersweet in its execution—every song tinged with sorrow, every kind word so profound when heard in the knowledge that a life has ended. In some ways, Henson’s wishes feel cruel—asking loved ones to celebrate so joyfully in the wake of such a sudden passing. But in another way, they’re a gift—an enlightened way of allowing not only his closest friends and allies, but also the world, to say their goodbyes. It reminds me of a joke from the 2011 legacy film, The Muppets, in which Kermit refers to laughter as the “third greatest gift” that can ever be given (behind children and ice cream, of course). If Henson’s memorial serves as a final testament to his life’s philosophy, then The Muppets serve as a lasting testament to his life’s work; as long as the Muppets can continue to bring joy to our hearts and laughter to our lives, then so too can Jim Henson.

Hello everyone, it’s my first go to see at this website,

and article is actually fruitful in favor of me, keep up posting these articles or reviews.

Does your blog have a contact page? I’m having a tough time locating it but, I’d like

to shoot you an email. I’ve got some ideas for your blog you might

be interested in hearing. Either way, great blog and I

look forward to seeing it expand over time.