Out of the many films in and out of competition this year at Cannes, I had to be one of the few people to greatly anticipate the new Juno Mak film Sons of the Neon Night, a film eight years in the making since its production began, and had almost reached the level of mythical status because of the long wait. Hong Kong’s very own Megalopolis, a big-budget, ambitious epic with an incredibly stacked cast including Takeshi Kaneshiro who had been in multiple Wong Kar-Wai films, and Johnnie To’s frequent collaborators Sean Lau as well as Louis Koo. Albeit this film is nowhere near as daring and off-the-walls as Megalopolis, I think for many Hongkongers, this would be the holy grail of Hong Kong cinema of the decade if it is done right.

Fast forward to Cannes, and picture this: hundreds of excited viewers lined up at the Croisette sometime around 11pm. We waited…and waited…we walked on the red carpet and stepped into a relatively empty Grand Theatre Lumiere. By the time the film began it was already nearly 1am, and the film ran until 3am. This is when the greatest enemy of a festival-goer had struck: sleep deprivation. Unfortunately for me, trying to stay awake was like prying open the metal gates that were my eyelids. It was a battle. But even with every awakening minute, I was completely lost with the film, not knowing how much I had missed. The two people sitting to my left and right were also sound asleep. By the time the film ended, half the audience had gone and the film received a measly 1-minute standing ovation. Negative reviews began pouring in the next morning. What went wrong?

Obviously it would be difficult for me to appraise the film and critique its form and contents since my mind was as fuzzy as clouds during the screening, but from what I can barely recall, I remember elaborate set pieces bold and overflowing with style, whereas the dialogues and the plot point seem to remain same-same throughout the film. Every character is a stone-cold hard-boiled man and every scene has either stern words or gunshots. I know I have probably missed most of what happened but I think that gives you the gist of what the film essentially felt like. Compared to Juno Mak’s previous and debut feature Rigor Mortis (2013), this is yet another attempt from him to hyper-stylize a previously well-established genre in Hong Kong cinema. With Rigor Mortis being an artsy riff on zombie horrors a là Mr. Vampire (1985) (I know, dumb English translated title), and then Sons of the Neon Night being his rendition of police crime thrillers such as that of John Woo and Johnnie To, but Juno Mak has neither the unique voice nor the cultural relevance that John Woo and Johnnie To have. As a result, Sons of the Neon Night pales in comparison.

More importantly, this brings us to a larger question at hand – what is up with Hong Kong cinema lately? As a cinephile and aspiring filmmaker from Hong Kong, this question haunts me in my every waking hour. Since the 2000s, the phrase “Hong Kong cinema is dead” has already been uttered. Hong Kong had done an incredibly run of films from the 70s to the 90s, going from early kung fu classics with Bruce Lee and period films from the Shaw Brothers Studio, to the 80s with the new wave – John Woo, Patrick Tam, Tsui Hark, Ann Hui, just to name a few – then the 90s hit us with auteurs like Wong Kar-Wai and Johnnie To, not forgetting to mention Stephen Chow being the successor to Hong Kong’s specific style of comedy first mastered by the Hui brothers. Entering the 2000s, most well-known filmmakers from Hong Kong seemed to have passed their primes while other film powerhouses in Asia like South Korea had taken the spotlight while Japan still retained the bigger spotlight. With the exception of Infernal Affairs, the next decades for Hong Kong cinema had been gloomy and murky, filled with cheap lowbrow comedies, one-note romances, and the occasional dramas that never took off. The last time a Hong Kong film had entered the competition in Cannes was Johnnie To’s Vengeance in 2009. And while Hong Kong has had better successes at Berlinale and Venice, a Hong Kong film entering competition is few and far between.

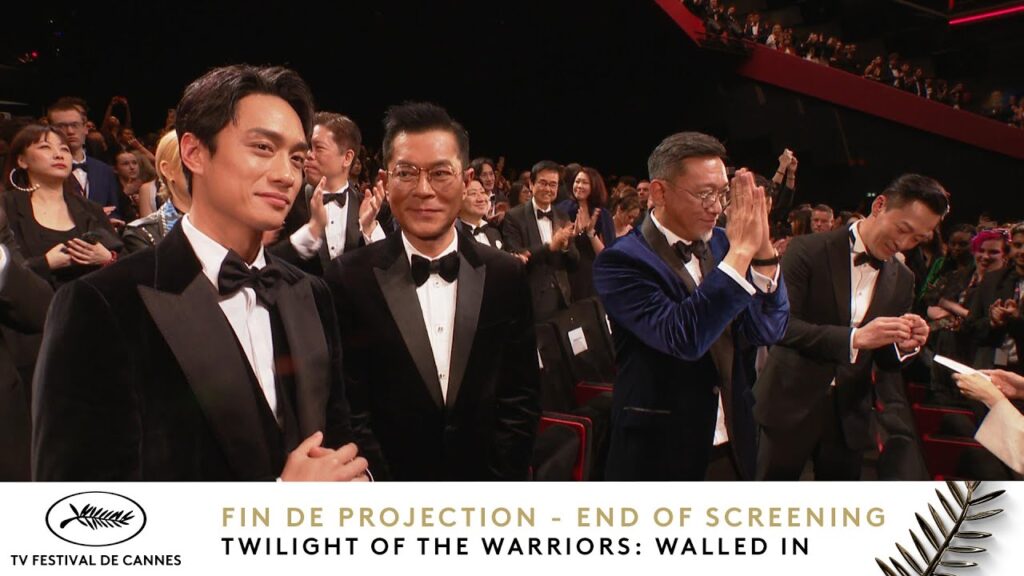

With the political turmoil Hong Kong experienced in 2019, many Hongkongers turn to film and music to anchor themselves onto a specific artistic idea in the hopes of a strong cultural identity. A curious phenomenon happens. Every single year since the pandemic, a specific film(s) would be hailed as THE film that is going to save Hong Kong cinema, and each and every time the film would not generate as much power as anyone hoped it would. In 2021 we had Jun Li’s social realist drama Drifting and Soi Cheang’s hyper-violent neo-noir Limbo, both films are fantastic, and neither of them broke into international fame. The social realist dramas continued with The Narrow Road in 2022, then In Broad Daylight and Time Still Turns the Pages in 2023 both made huge waves in Hong Kong but didn’t have much staying power beyond that. A desperate attempt to reinvigorate nostalgic action blockbusters with Twilight of the Warriors: Walled In was semi-successful, at least in Japan. Other “oh! Hong Kong cinema is so back!” films include the Sparring Partner and the Last Dance, which flew away in the wind after a few months. The next film everyone would point their fingers to is, of course, Sons of the Neon Night.

Truth be told, I knew Sons of the Neon Night wouldn’t do that well in Cannes, but I was even more shocked by the overwhelming negative response. I think it is partially due to the inconvenient late screening time, and also partially due to the general audience not being well-versed in Hong Kong gangster crime thrillers, but I think it is mostly Juno Mak’s tender lack of imagination. There are only a few ways Hong Kong can break out of this awkward mold: one is to completely commit to the bit and collaborate with China with big budget productions and make something big and accessible like Ne Zha 2; next is to rebel and go completely opposite way and continue down the political spiral; or, forget about appealing to general public and only go for festivals, but this requires a more ‘arthouse’ (a much misused word, I will avoid this word as much as I can) sensibility and more challenging form and content. If Wong Kar-Wai got his start at Quinzane (Director’s Fortnight), I’m sure the next Hongkonger filmmaker to end up in Quinzane will go places too. On occasion there is a lightning-in-a-bottle situation like India with RRR but that bears the risk of being a one-hit wonder. Either way, the problem is with itself, Hong Kong government is still not giving the film industry the funds it deserves while film education continues to fall behind, I yearn to see the day where movie-going becomes popular again in Hong Kong, where everyone is dying to tell stories and make art, and where being a filmmaker in Hong Kong means being inspired and to inspire.