They say that life is stranger than fiction. It’s also so much more uncomfortable to watch.

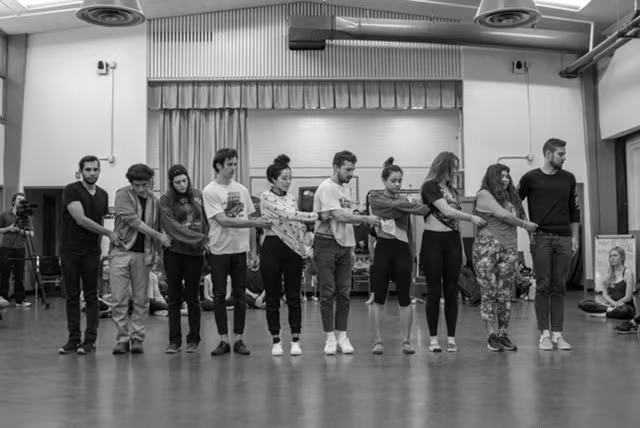

In 2018, Shia (I Am Not Famous Anymore) LaBeouf held a weekly acting workshop at the Slauson Recreation Center in South Central Los Angeles under the guise of bringing a positive community organization to the people of the neighborhood. Over the course of several years LaBeouf cultivated a tight-knit crew of dedicated acting students, establishing a rag-tag theatre company and ultimately writing, directing, and staging a social-distanced production about COVID-19 at the height of the pandemic. For this group of local nobodies, it’s safe to say that none of their lives would ever be the same.

If Leo Lewis O’Neil’s Slauson Rec has achieved anything of cinematic importance, it’s through the way in which it inflicts upon its audience a similar kind of anguish and humiliation to what LaBeouf’s young protégés also endure over the course of the documentary’s two hours and twenty-five minutes of screen time. But these individuals—largely aspiring actors, or social outcasts just looking for a place to call home—devote themselves so wholly and earnestly to such a lost cause that we cannot help but feel we have devoted ourselves to it as well. Whether withstanding verbal abuse or physical assault from the unstable actor turned would-be theatre director, we feel what they feel: insulted, violated, de-valued as human beings. We empathize with them because as the credits roll at the end of the film, we believe that we too have survived a truly bizarre and unpleasant ordeal.

The way LaBeouf’s devotees look up to him is chilling; the sacrifices they make to attend his classes are difficult to comprehend (one woman is so dedicated, she forgoes time with her dying mother to attend rehearsals, though Shia later decides to cut her from the production after she finally does take leave for the funeral). The entire process is like watching a cult slowly develop from the outside—unsure how the people who get sucked in can fail to see the gross imbalance of power that is so clear from an audience’s perspective. Brief interviews with the youngest member of the company, a girl from the local community, start off as amusing commentary—she brushes off the long days of rehearsing in the hot sun and the erratic behaviour of their director, who regularly abandons these sessions in a fit of frustration. But as the film progresses, her nonchalance begins to suggest something more sinister; she’s been instilled with the attitude that if they create something really spectacular, all the pain they’ve suffered will have been worth it. The abuse is a small price to pay for the rewards that LaBeouf vaguely promises them: namely, eternal greatness.

Though the troupe begins as something more experimental—devising group dances and strange performance pieces—the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic sends them scrambling for a way to continue creating. When their attempts to write a play over Zoom fail to bear any fruit, LaBeouf decides to write the piece himself. The remainder of the film follows their sixty-plus days rehearsing a COVID-friendy mixed-media play, to be performed in a parking lot and ultimately attended by major Hollywood agents and such notable figures as Sean Penn.

But the rehearsals are truly brutal. Their makeshift performance space consists of a dozen folding chairs and a couple of large white tents pitched in a sun-baked parking lot. And the only thing more painful than watching the company cook in the heat, day after day, pouring their souls out over Shia’s script, is watching the man himself strut around, shirtless, demanding they take a scene again, giving contradictory notes, needling his actors to no end. There’s something inherently humorous in the way the days flick across the screen with each day more of the same: LaBeouf storms off set, the rest of the cast and crew left staring at each other, dumbfounded. Acting advice devolves into personal attacks and petty arguments. The participants start to abandon ship, one by one. Even the most loyal among them ultimately reach a breaking point.

The doomed theatre company fell apart in 2020, rather predictably, around the same time abuse charges were leveled against LaBeouf.

Slauson Rec is in many ways a testament to the way that celebrity eats away at the soul, hollowing out what makes someone who they are until their humanity dangles precariously by a thin string of personhood. The question remains: how can we continue to look upon this person with any sense of compassion? And if the only way to do so is by reminding ourselves of the fate that so often befalls child actors, does that mean they deserve a life-long pass to treat others with such a blatant absence of decency?

The film’s most heinous offense lies in its utter lack of self-awareness. O’Neil introduces himself early in the movie as a person initially drawn to the acting workshops because of his personal interest in LaBeouf, and because of his admiration of LaBeouf’s work as a performance artist. O’Neil attended classes from the start, ingratiating himself with LaBeouf, and eventually began recording the workshops for archival purposes. There’s an argument to be seen for documenting the notorious actor through the lens of comedy (if he weren’t actually endangering his “students”) or as an attempt to unpack and comment upon the inherent narcissism at the heart of a superficially altruistic act. Or, more simply, as a revealing character study. Instead, O’Neil provides LaBeouf the opportunity to speak for himself, to apologize to those he wronged. LaBeouf conjures an air of regret for his actions in an intimate interview at the conclusion of the grueling flick, during which an off-screen conversation with his partner as she returns home from a routine prenatal check-up attempts to humanize the man who has spent the past two and a half hours tormenting a group of young actors. But we cannot so easily forget that these were people who sought nothing more than his approval and a little of his time, and instead found themselves a community of punching bags for a man whose self-hatred runs so deep, it spills out and drowns the many well-meaning but misguided individuals who earnestly flocked to him in search of mentorship and a place of refuge in an increasingly self-isolating world.

“We are not friends,” he says to the ones who talk back. When someone attempts to challenge him, LaBeouf makes it clear that their relationship begins and ends with the craft of acting; that his love for them is in no uncertain terms conditional. That any sense of camaraderie between them can evaporate just as quickly as it calcified.

Shia LaBeouf’s continued involvement with Slauson Rec—mainly, his presence at its premiere screening as part of the Cannes Classics section of the film festival—hints not only at the actor’s unnerving ability to disconnect from his own image, but also at a masochistic need to subject himself to his own horrific behavior. There’s a misbegotten notion that simply acknowledging one’s failures and wrongdoings goes a long way in absolving them of their past mistakes. And certainly there’s something to be said for a sincere apology, or for time spent reflecting upon past behavior in an effort to implement some serious change. But if we allow ourselves to believe that our own suffering can somehow alleviate or cancel out that which we have caused others, then we are all in for a world of hurt.