Believe it or not, I have done homework prior to the viewing of this film. I’ve seen Markiplier, Jacksepticeye, and even Hololive’s very own virtual streamer Oozora Subaru play the game ‘Exit 8’. Hell, I could even tap back into the memories of when I was navigating through the ever-busy Shinjuku station in Tokyo during my trip there.

Video game adaptations are notorious, and for good reasons. While games and films are obviously two separate media, the greatest difference is that the former is a playable immersive experience, which means the narrative is in control of the player, while the narrative of a film is written, and the viewer has no say in what would happen. This means awkward silences, lulls, and repetitions are acceptable in games since they are the direct result of the player’s decisions; this doesn’t apply in film. The average film *production* professor would tell you to trim the fat, but really, fat is part of the game. This is where adapting ‘Exit 8’ gets tricky, since the game is literally about being stuck in an eerie walkway in a metro exit. Every time the player walks through that bit, it would entail several things: a bald salaryman walking past with a briefcase, a photo booth, several doors, vents, and posters. More often than not, an anomaly would occur, such as the posters being suspiciously large or a door handle being placed at the center of the door, or worse, a flood or an invisible ninja attack. In those cases, the player must turn back in order to advance to the next level. Once the player goes past 8 levels, they successfully escape.

A game with such a tedious gameplay and requiring this much patience would normally yield an exhaustingly bland film. Several repeats of the main character walking the same hallway would get stale. But the real surprise is that Genki Kawamura is able to attach different emotions and tones to each ‘walk’ the main character does so that it would never get stale. Our main character, named “The Lost Man,” starts off confused, puzzled, scared, then accomplished, fails, and then goes back to fear, and goes through a wide array of mood swings. This is then paired with gracefully smooth steadicam shots that glide from space to space, pointing at shiny surfaces with meticulously erased camera reflections. Then, just as it’s about to get redundant, the film flips the whole narrative around and introduces a brand new character, thereby expanding the lore that was never there in the game. Somehow, with the help of cheesy scares and melodramatic cries, the film manages to hold itself up for 95 minutes straight. From long takes to POV shots, Kawamura pulls enough tricks out of his hat so that the film would only teeter on crumbling apart and nothing more.

The most interesting point, however, is the exceedingly fascinating, completely out-of-nowhere element of fatherhood slapped onto the film. The original game is completely devoid of lore and meaning, and I find this film’s attempt at conjuring meaning out of nowhere to be hilarious but somewhat commendable. Basically, this entire infinite loop hallway thing represents the main character’s anxieties of being a father. The opening scene reveals his girlfriend telling him she had just given birth through a phone call, and later in the film, the main character runs into a little boy and then becomes the boy’s father figure. At this point, we must dive further into the deeper issue that is the low fertility rate in Japan. Media like this is emblematic of the recent media push towards pro-family attitudes.

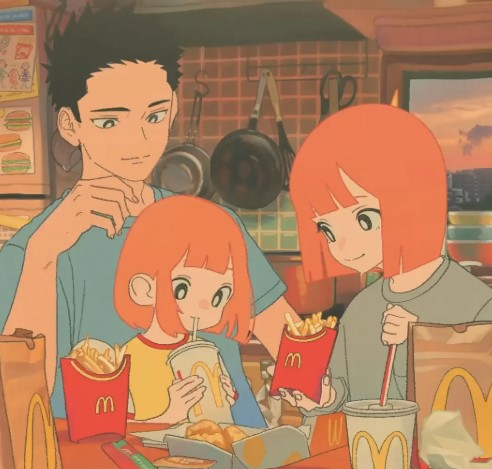

In the last decade or so, fewer and fewer children are being born in Japan as well as other nations in East Asia. To combat that, pro-family media begins to roll out. They appear in different shapes and colors. There is the gentle reminder of the joys of having children, such as the much-debated McDonald’s ad that whipped Twitter up in a storm a few years back to animes such as Spy x Family. Meanwhile, animes such as Darling in the FranXX shamelessly urge the youth to procreate, only through a half-baked story. The director of this year’s in-competition Renoir, Chie Hayakawa, debuted with her film Plan 75, which expresses anxiety over Japan’s rapidly aging population, shedding light on the opposite side of the spectrum in the plight of the low fertility rate. Unsurprisingly, new Japanese media react by skewing towards emphasizing pro-family, pro-romance, pro-relationship narratives. Such can also be seen in the other out-of-competition film this year, Love On Trial, a film that explores the courage of a J-pop idol who has a boyfriend even if that gets her sued. During Exit 8, one must wonder what the demographic is. Since teens are usually the consumers of such games, the film basically urges teenage boys and young adult men of Japan that “it’s okay, in fact, it’s pretty awesome to have a child. I mean, you get to be with Nana Komatsu. What’s not to love?”

Either way, to attach a pro-family narrative in a cheesy horror game adaptation is bizarre enough, but I think the next most head-scratching moment would be when the main character simply ditched his backpack and never picked it up for the rest of the film. I guess that’s all he had to sacrifice, right?