Let me say this right off the bat: Megalopolis is objectively and technically a disaster of a movie. It bites off far too much for it to chew, it has awful looking special effects, the plot is messy, the performances are uneven, and there are no wholly positive depictions of any female characters. With exception to his treatment of female characters, which to my knowledge has been an issue with much of Coppola’s filmography, many of the film’s faults can actually be interpreted as self-referential tools Coppola employs to critique himself, the art of cinema, and society as a whole. Megalopolis is a masterclass of total disaster, and whether people appreciate the mess and the questions that may arise from it has already become a polarizing discussion.

Necessary Context

Before I start to continue talking about the movie itself, I want to think back on Megalopolis’ history. Francis Ford Coppola has allegedly thought about making this film in some capacity or another for 40 years, ever since he was at the helm of Apocalypse Now. Megalopolis has allegedly gone through hundreds of rewrites in that time, and was ultimately only greenlit after Coppola sold his lucrative wine estate so that he could self-finance the film for $120 million. It is safe to say that this film is not just some “phone it in, cash the check” project for the 85 year-old director… and the film may also be his last.

With all of that in mind, I want to talk about one thing that dictates the relationship between an artist and an audience in every form: trust. Audiences trust that the best directors make every decision for a reason and with a purpose, and along the way that trust is either strengthened or diminished depending on how it affects the story and the audience. So this begs the question: does the audience trust Francis Ford Coppola, or not? After all, he is the director of bona fide classics such as The Godfather trilogy, Apocalypse Now, The Conversation and Dracula… but he is also responsible for some infamous failures, including One From the Heart and The Cotton Club. Even some of Coppola’s successes were first thought to be disasters, such as with Apocalypse Now, which was a famously chaotic production that went through a series of drastic and tragic setbacks. And now, as Megalopolis finally premieres in Cannes, rumors swirl about Coppola’s erratic behavior on set: smoking copious amounts of weed, managing time poorly, kissing extras on set, etc etc.

My point here is this: Megalopolis is a movie that demands the audience to trust in Coppola for it to have any meaning or weight. Though I must admit that this faith is certainly tested at times within the film’s 138 minute runtime, I believe that audiences will be able to genuinely glean some poignant themes from Megalopolis if they just trust that the director with 40 years of experience and multiple timeless classics under his belt does indeed have a method to his madness.

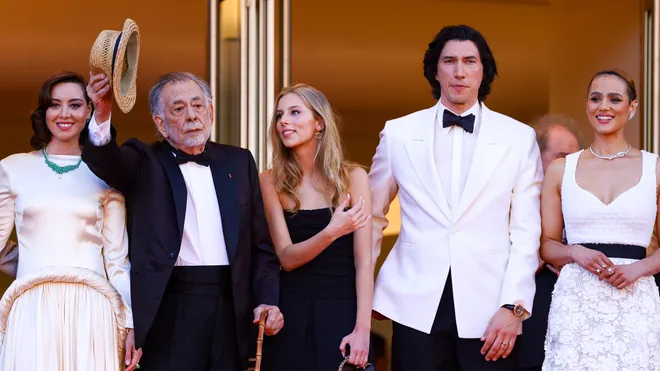

Left to Right: Aubrey Plaza, Francis Ford Coppola, Romy Croquet, Adam Driver and Nathalie Emmanuel

Review

If there is one word to describe Megalopolis, that would be an apt one: madness. The film takes place in the paradoxical “New Rome”, which is essentially a futuristic, gilded, semi-modern New York that houses a contemporary Ancient Roman society. Megalopolis stars Adam Driver as Cesar Catalina, a visionary, coveted, almost messianic artist and architect who seeks to use his newest innovation, a material called “Megalon”, to construct a utopian society. Cesar is opposed by Mayor Franklyn Cicero (Giancarlo Esposito), who seeks to retain the old guard. The mayor’s daughter, Julia Cicero (Nathalie Emmanuel) falls in love with Cesar, dividing her loyalties and further complicating the struggle for New Rome’s future. The film is also riddled with other star-studded castings, including Aubrey Plaza, Shia LaBeouf, Dustin Hoffman, Laurence Fishburne, and Jason Schwartzman; most of whom come into conflict with Cesar’s ambitious plans out of jealousy or greed.

The synopsis above may make it seem like the film has grand things to say about our society at a fulcrum as it grapples with revolutionary new technology that threatens to push us one way or another… and in a way, it does. When this commentary is conveyed on the page and in the plot of the story, it mostly comes across as a mere aggregate of shallow concepts, too jumbled to be cogent in any way. We see an empire fall through its opulence, promiscuity, greed, jealousy, ambition, and a myriad of other symptoms, but we never get to the root of any of these problems. Though Megalopolis makes attempts to speak to American politics and socioeconomics, these attempts are far too vague and generalized to feel pointed in any way. Instead, the film’s most potent dialogue about these issues is molded by Coppola’s reflective contemplations through metatextual manipulations of the cinematic form itself.

It is easy to see Adam Driver’s character, Cesar, as a representative of Coppola himself: a creative with maddening ambitions and nearly infinite resources. Cesar is surrounded by the future and haunted by his past, obsessed with his utopia, and disillusioned with his society. He is a dreamer with his head in the clouds. When Cesar announces his designs for his “Megalopolis” to society, chaos unfolds as those around him grovel for power and New Rome sinks further into promiscuity and disorganization.

Those words that describe “New Rome” during its fall also describe Megalopolis: messy, unfocused, and overly promiscuous. Dialogue is almost exclusively wooden and delivered unenthusiastically. Characters occasionally snap off into total non-sequitur, one line philosophies that feel as if Coppola scribbled them down somewhere whenever he was high and insisted they be shoehorned into a scene. Certain scenes are written as if they are meant to be a dry comedy, yet the punchline never comes, and the actors seem unsure how seriously they are supposed to take the material themselves. Characters speak in English, Latin, and Shakespearean quotes. Near the end of the film, Coppola has sequences where frames are split into thirds, and there are multiple shots where 5 or 6 frames are composed and faded onto one another, filling quite literally every white space on the screen. There are psychedelic trips, boner jokes, a seemingly random instance of Shia LaBeouf cross-dressing (potentially a reference to actors of Shakespeare’s time?), and nearly all of the CGI looks like it was made by a YouTuber for a no budget sci-fi fan fiction. The film at times feels cinematic, at other times like television, and sometimes like a stage play. Oh, and at one point during the movie (MILD SPOILER AHEAD), while Cesar is at a press conference, a live-performer in the theater literally walked up in front of the screen and asked a question, to which Cesar then replied.

The film is a cacophony, to be sure, but I believe the far more interesting question is whether or not Coppola intended Megalopolis to be exactly the cacophony that it is. I realize that suggesting a director may have made a bad movie “on purpose” is often a total copout, but please stay with me on this.

Cesar’s “Megalopolis” feels like it is an allegory for Francis Ford Coppola’s Megalopolis. A seasoned dreamer is obsessed with his vision of perfection until he realizes that this perfection is ultimately unattainable, and the pursuit of this perfection blinds that dreamer to the problems that proliferated in the meantime. Megalopolis appears to the naked eye as a film about one too many things: the many maligned focuses of American politics, the downfall of society, the futility of utopias, the faults and corruptions of our leaders, the pursuit of love, the fear of death, etc etc. Perhaps, at one point in this film’s 40 year long incubation, Coppola truly thought he could make a film that would succinctly and adequately address all of these things, and maybe also solve world hunger along the way. Perhaps, during one of this film’s many rewrites, Coppola realized the futility of this effort, and decided to change direction. Instead, he made a movie that deliberately failed under the weight of those ambitions in order to illustrate this realization through a form of cinematic self deprecation. Perhaps Megalopolis is Francis Ford Coppola’s way of exposing his own ambition’s ugly head to the world, a jab at his own hubris as an artist, and a final warning to ambitious filmmakers that continue to play with more and more revolutionary technologies as time goes on.

The way Coppola manipulates and bloats the cinematic form with digital effects, crowded superimpositions, gratuitous fades, split frames, and even a live performance component all speak to Coppola’s intent. Much like the late stages of the fallen ancient Roman society that Megalopolis so often refers to, Coppola’s techniques are scattered, divided, unrestrained, grandiose, and overly indulgent. To the naked eye, Megalopolis appears as if it wants to be a world bending film. A cast stuffed to the brim with megastars. A setting that is both ancient, modern, and futuristic. Frames that require the viewer to look ten places at once. A comedy that is also a science fiction epic that is also a political and social commentary. A film that is cinema, television, theater, and interactive entertainment all rolled into one. Though on the surface, it looks like Megalopolis suffers because of this often incoherent hodgepodge, the intentionality of these choices seem to reflect Coppola’s fears about the pitfalls awaiting the future of cinema and society as a whole, and that realization makes the conversations you may have after watching Megalopolis a whole lot more interesting.

If it were any other filmmaker, I think it might be harder to argue this point. However, with a filmmaker of Coppola’s stature, on a work that was supposed to be his magnum opus, it is hard for me to believe that every choice is not deliberate, especially when these choices align so seamlessly with the themes of the film. And if every choice is deliberate, then has Coppola, a master of cinema, just gone completely mad and lost his touch? Or is he trying to say something that is, at a glance, harder to understand?

The debate between some of my colleagues and I has been whether Coppola truly intended for Megalopolis to be ironic, or if our meta-textual interpretation of it is just our projection onto a movie that was genuinely made in poor taste. If Megalopolis truly wasn’t “in on its own joke” as I believe it was… does it matter? Should we care whether or not Coppola actually tried to make a “bad” movie, and should that intent change the way we look at it?

For many of the reasons listed above, plus more, Megalopolis can be and will be seen as a “bad” movie by many. For others, Megalopolis will be a film that uses an entirely new, unique, and inventive set of tools to bend the medium and convey its message, making it a masterpiece in its own right. I find myself caught somewhere between these two sentiments: I rolled my eyes during the film, yet I keep finding myself drawn to discussions about it afterwards, which makes the film’s effect all the more fascinating. My more optimistic interpretation of Coppola’s intent has led me to enjoy the film a lot more than others may have, and has kept me thinking and talking about the movie for days, which is ultimately one of the highest compliments I can give to any film. Megalopolis is a huge swing and a miss, but whether it was an attempt to illustrate the likelihood of missing when taking huge swings is ultimately for the audience to decide.

Like the film, I fear this review has also become too long winded, ambitious, and scatter-brained, so I will conclude here by encouraging all who have made it this far to go and see the final project of an absolutely legendary filmmaker with an open mind, and I hope you enjoy it!