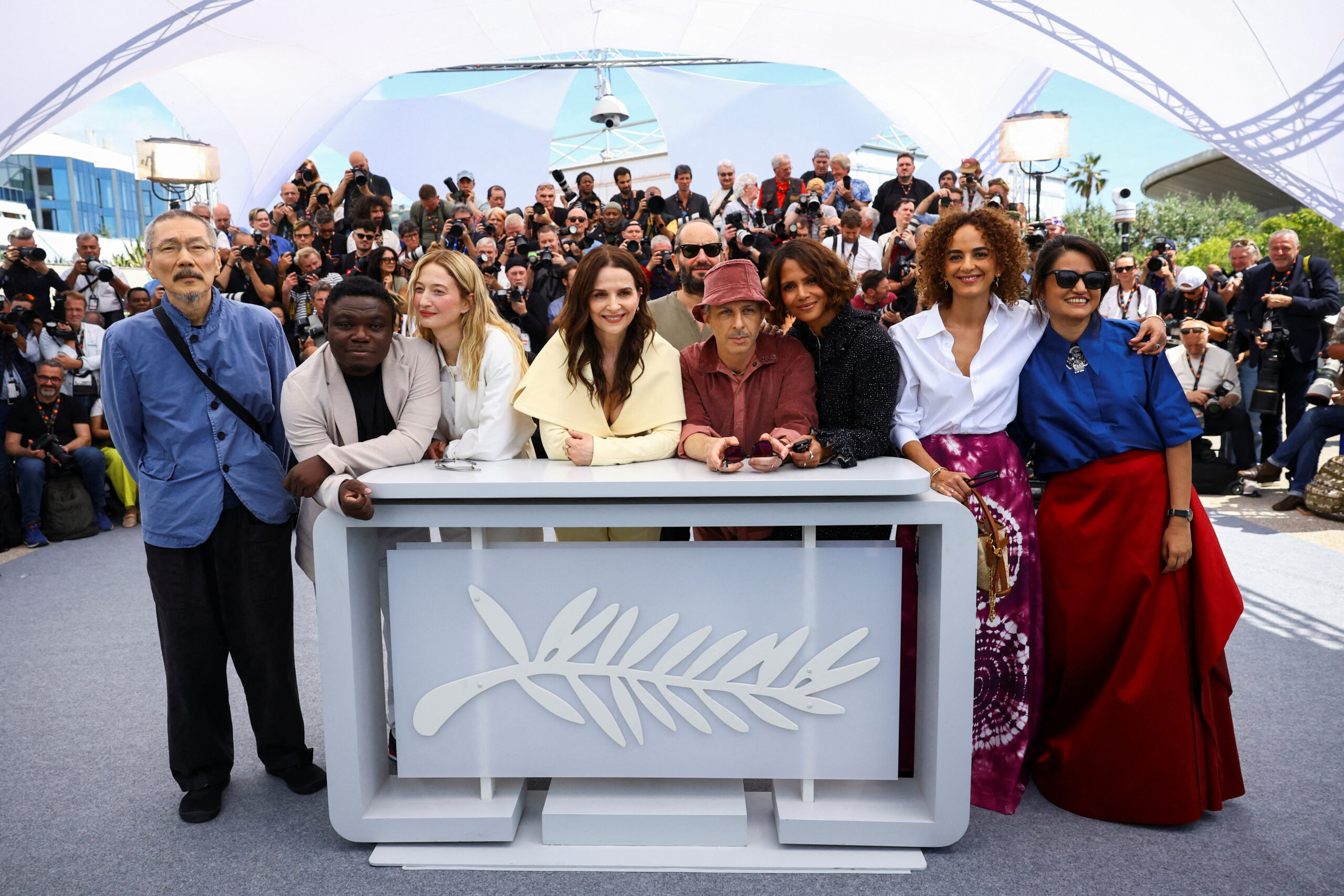

The Cannes Film Festival has come to a close, and with its conclusion came the handing out of this year’s awards. The jury’s process has always been enigmatic, with rumors swirling of dramatic infighting and dictatorial jury presidents. This year’s jury, led by president Juliette Binoche, was not immune from these allegations: the top prize was given to Jafar Panahi’s It Was Just an Accident, a filmmaker whom Binoche has not been shy to praise in the past. It’s impossible for the jury to exist in a vacuum. They are not sequestered in a conclave (much to my disappointment); they’re on the ground, with the rest of us, talking about what they’re watching.

In a sense, we at USC Cannes Classics are our own jury. Like the official jury, we watched a boatload of movies over our twelve days at the festival, and like the official jury, we have diverse opinions. The process of articulating our award winners, though, was slightly different than the jury’s. We conducted a virtual survey ranking films, performances, scripts, and directors. Responses were assigned numerical values based on their ranking, and based on these totals, and a more holistic review process, awards were decided on by me, our self-appointed jury president (sorry, guys!). We had some ground rules: no film would earn more than one award, and we did not limit ourselves to films in competition. Additionally, instead of giving a Best Actor and Best Actress prize, we awarded Best Lead Performance and Best Supporting Performance. Our award winners, with responses by some of our jury members, follow below. Keep in mind that we are far better and more important than the real jury, and our awards are perfect and unimpeachable.

Best Supporting Performance (TIE): A$AP Rocky (Highest 2 Lowest) and Tahar Rahim (Alpha)

By Arjun Fischer and Garrett Michaud

A$AP Rocky—the Grammy award winning multi-hyphenate rapper, fashionista, celebrity husband extraordinaire—returned to the Croisette for the first time in a decade this year, making a foray back into the world of acting. He’s the star of Highest 2 Lowest, Spike Lee’s remake of Akira Kurosawa’s 1963 classic High and Low, which played out of competition at Cannes this year. A$AP plays rapper Yung Felon in the film, a name that A$AP changed from the original script during a collaborative production process with Spike, bursting onto the screen in the third act of the film to go toe-to-toe with Denzel Washington in an audacious final act that includes a rap battle, (double) double dolly shots, music videos, and a tour de force performance from A$AP that is one of the standouts of the festival at large. Spike’s latest film often struggles to have ideological coherence, but finds its footing through Yung Felon, channeling Kurosawa’s class commentary while injecting a healthy dose of modern New York through the Harlem-born A$AP’s performance and palpable chemistry with Denzel. “I was born for this. I’m not gonna waste nobody’s time. This is what I do,” he said about acting opposite the legend. The metatext of the performance is also unavoidable: with A$AP Rocky’s real-life trial for assault concurring with the shooting of the film in which his character Yung Felon awaits trial for the kidnapping at the center of the story. In February, A$AP was found not guilty, and immediately jumped into Rihanna’s arms in a blissful embrace. He brought that same exuberance to the red carpet, the silver screen, and everywhere in between this year at Cannes, most importantly putting in a Spike Lee star-making performance worthy of the rich history of greats like Denzel, Samuel L. Jackson, and Wesley Snipes that precede him.

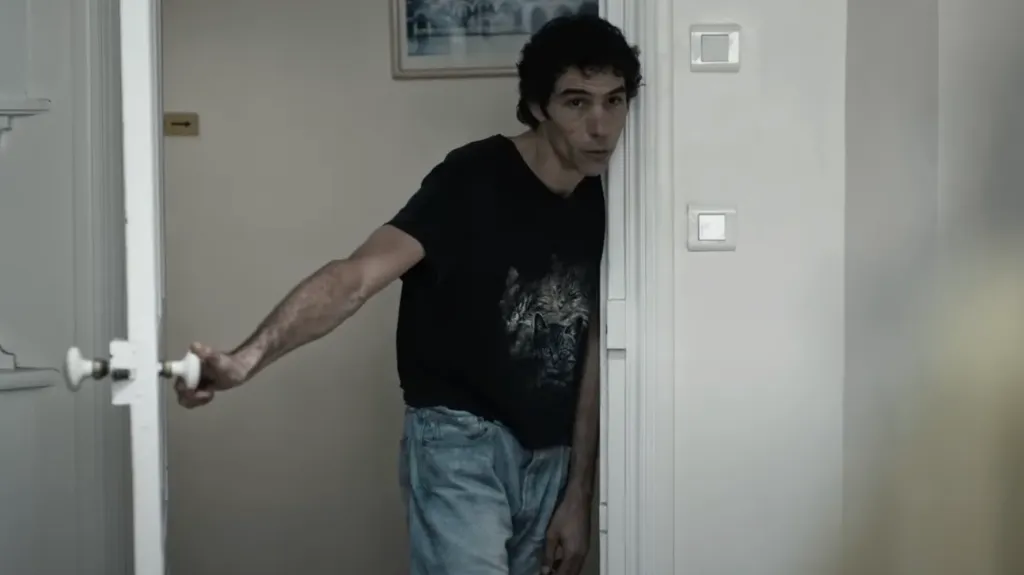

There is an obvious comparison to be made between Tahar Rahim’s physical transformation for his role as Amin in Alpha and that of actors like Christian Bale in The Machinist or Joaquin Phoenix in Joker. His weight loss and body transformation for the role are astonishing, as he doesn’t even look like the pictures that come up when you search Tahar Rahim on Google, but he does much more than transform his looks for this role. Rahim brings a level of humanism and charm to the role that is honestly the most memorable part of the film. When we see Amin through Alpha’s eyes, Rahim maneuvers in a horror monster manner that shows Alpha’s unease towards him at first. When we see him through Maman’s eyes, we can see and feel the charm and joy Amin brings to her world, and we can see why Maman loves him so much. Although there is this duality in the performance, both perspectives feel true to Amin’s character. Rahim is able to masterfully explore the multitude of persons that exist in any human being in a way that feels genuine and cohesive. This level of mental character study and physical performance is rare in a film, and Rahim’s performance alone makes Alpha a worthwhile watch.

Best Lead Performance: Sope Dirisu (My Father’s Shadow)

By Zach Sullivan

In a sea of terminally online hypermasculinity, Sope Dirisu’s performance as Folarin in My Father’s Shadow was incredibly refreshing. As a father showing his sons through the city of Lagos and a changing Nigeria, Dirisu often acts as the guiding light of the film, offering the perfect balance between sternness and patience that only a parent could provide. His ability to peel back the layers of Folarin just enough to offer audiences a peek into a rich, nuanced perspective all while still maintaining a certain level of distance from others is truly a sight to behold.

Best Screenplay: Joachim Trier (Sentimental Value)

By Colin Kerekes

Contrary to the court of public opinion, Joachim Trier’s The Worst Person in the World never truly stuck with me. Perhaps I was not at a certain period in my life to resonate with the subject matter, but as a fan of flawed, borderline unlikable protagonists, I found Julie to be dull and her journey ultimately too connected to romance rather than all the other aspects of growing older. So, I ventured into Sentimental Value wary yet hopeful. My hope paid off as Trier managed to remedy all the issues I had with The Worst Person in the World with an expertly written screenplay. He decides to again tackle the ideas of growing older, exploring relationships, and wrestling with one’s shortcomings – this time, centering these themes within the family system. Gustav (Stellan Skarsgård) fulfills the tortured artist stereotype in his inability to properly articulate his feelings with others, particularly his daughter Nora (Renata Reinsve). Hence, feelings and interpersonal relationships are revealed, like breadcrumbs, through his art. Likewise, Trier’s script itself ensures that no time is wasted when it comes to character development. Though new plot threads are being introduced constantly, whenever one character is explored, another is indirectly examined as well. Trier’s work becomes quite meta in this sense. As fragments of the self are explored through Gustav’s script or Nora’s acting, Trier employs each character in a way that is symbiotic to one another. As a result, his screenplay functions like a well-oiled machine. Everyone exists as a piece in a puzzle, and no piece is unimportant to the grand scheme of things.

Jury Prize: Die My Love

By Matthew Chan

The easiest way to describe Lynne Ramsey’s Die My Love would be to lobby comparisons to John Cassavetes’ A Woman Under the Influence, though this reads to me as a fundamental misinterpretation. While that film explores mental illness from the outside, Ramsey’s film takes place from the inside as Lawrence’s perception of reality is so thoroughly warped through the lens of postnatal depression. And what comes in hand with the complete subjectivity of Ramsey’s picture is a wonderful rupturing of narrative logic as her works finally makes a turn towards the fully elliptical: histrionic emotion, heartfelt singalongs and sensuous, feral, pastoral imagery strung together under the pretense of a reality altered. Rarely do you see an American production so attuned to the conditions of body and the physicality of its performers, contorting and exposing Jennifer Lawrence and Robert Pattinson into shapes and states typically reserved for the private eye. And rarely do you come across a work as keenly aware of how the mind dictates experience and how the body, in at times concerningly involuntary fashion, can express desires the self can’t even begin to process. I’ll be hard pressed to find another film this year with as much blood running through its veins.

Best Director: Bi Gan (Resurrection)

By Enoch Lai

Known for his ethereal mega-long takes and painterly framing of rural China, Bi Gan hams it up with his new film Resurrection, where he invites us into a time-jumping, fragmented, never-ending dream that shape-shifts into different forms and styles every few scenes or so, having the most intricate and aesthetically challenging directing in this year’s festival.

Grand Prix: Sound of Falling

By Colin Kerekes (excerpted from review)

For me, the exploration of desire engenders a cinematic work with a special sense of compassion. Hence, it is fascinating that a film so cold and ghostly as Mascha Schilinski’s Sound of Falling can travel so internally into the depths of the honest human psyche. It is a sprawling behemoth of a film encased within the confines of a farm in Altmark, Germany. The farmhouse that constitutes this space is both transformational and ageless. The walls. The floors. The courtyard. The lake. They are at once antiquated and mutable, still and fluid. By keeping all characters of this ensemble piece affixed to a single yet multi-faceted location, Schilinski effectively interweaves the lives of four generations of women – Alma (Hanna Heckt), Erika (Lea Drinda), Angelika (Lena Urzendowsky), and Lenka (Laeni Geiseler) – all saddled with their own forbidden desires. To condense Sound of Falling the best I can, it is a film that looks outward and successively, inward. Halfway through the film, Angelika, inhabitant of 1980s Altmark, says that the men of the farm “thought they were looking at me, but I was looking at them.” Even as her back is turned, she notices being noticed. Her awareness embodies the control Sound of Falling has over the viewer. Characters repetitively look into the center of the camera, generating an uneasy consciousness of the human spirit. A glance is an assertion – what you see in the film is an extension of your own habits, and those habits are not just distinct to you, but all that came before and will come after you as well. Your desire is not just your own.

Palme D’Or: It Was Just an Accident

By Camden Rider

On paper, it’s easy to see why Jafar Panahi’s It Was Just an Accident would find success. The film marks a shift for Panahi away from more explicit autofiction. Many of his previous films, including Taxi (2015) and No Bears (2022), feature Panahi as a fictionalized version of himself, interacting with his community. Here, though, Panahi remains behind the camera, telling a story of community, torture, memory, and trauma. Given Panahi’s former imprisonment and the ban on his filmmaking from the Iranian government, there are elements of his own story in It Was Just an Accident, yet the distance between his own body and the actors’ bodies provides Panahi with a sense of mediation. The memories of the central characters’ torture are complicated and contradictory, as are their responses when confronted with the appearance of the man who tortured them. Or is it? Doubt seeps into their minds as they consider whether or not their own trauma can be resolved by punishing someone else, someone whose past they have no way to verify. Panahi’s mastery of tone, script, and cinematography allows these tensions to shine, creating a film that is at once tense and cathartic.