Die My Love opens still and contained. A static shot enveloped within the walls of a rural home drenched with flowers and nostalgic flair. Grace (Jennifer Lawrence) and Jackson (Robert Pattinson) stumble upon the scene, though their arrival isn’t really stumbling, and instead confident and premeditated. Really, the only time in the film where their actions can be described as meticulous.

Then, static becomes fluid. Shots are quick. The pace of the edit is electric. The score is loud. Grace and Jackson’s bodies are loud. Everything on screen is marked by ferocity. A title card backdropped by a burning forest serves as a statement from Lynne Ramsay to the viewer that Die My Love will be as spontaneous and dangerous as a dancing flame.

Ramsay is a master at the mood piece. We Need to Talk About Kevin drips with dread, every scene possessing a special bleakness and isolation – Tilda Swinton’s maternal misery is palpable. Morvern Callar plunges the viewer straight into ambiguous grief. Morvern is a tough shell to crack, but you feel right there with her even if her actions insinuate self-interest.

Die My Love falls quite comfortably within the mix of Ramsay’s filmography. It is a narrative that is only effective by placing its hands on the sides of the viewer’s head, violently shaking them, forcing their eyes open like A Clockwork Orange, and arousing an insanity and frustration that can only dream of coming as close to Grace’s inner turmoil.

Jennifer Lawrence physically expresses Grace’s postpartum depression with the subtlety of a sledgehammer – there’s no need to infer the degree of her anger, sexual frustrations, or loneliness, as no movement is perfunctory. The visual aesthetic of her home feels about 60-70 years disparate from the film’s other locations like the baby shower or the psychiatric ward. She is trapped, fixed to the outskirts of civilization with a crying baby and buzzing flies. Her only escape is through complete bodily release.

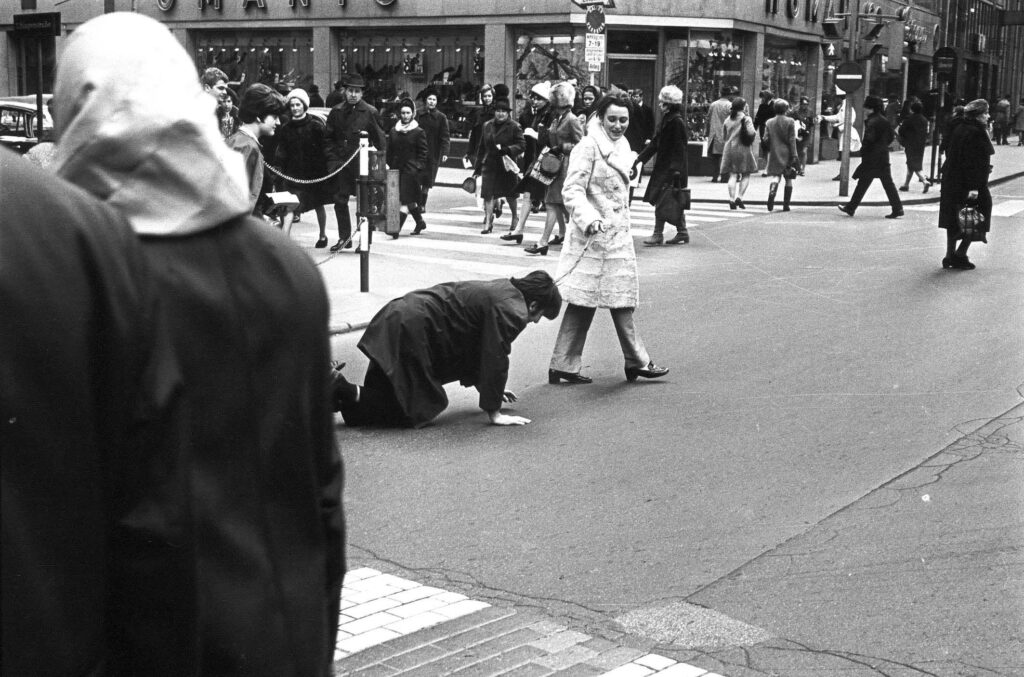

Much of her performance, its extremity matched by Robert Pattinson when necessary, feels rooted in the theatrics of performance art. Watching her crawl through a field of tall grass, biting on a blade, enhanced by the charged purr of a wild cat, reminded me of Valie Export’s From the Portfolio of Doggedness, where export transforms man into animal by walking artist Peter Weibel on a leash through the streets of Vienna.

Another artist brought to my headspace, more expressive yet thematically pertinent, was Olivier de Sagazan, made notable by Transfiguration – a work which involved Sagazan drenching himself in clay to transform from human to inhuman in real time. Evidently, Ramsay is interested in considering how the mind influences the body, and all the ways in which the body becomes a primary mode for communication when words cannot suffice.

Grace takes on many different forms in Die My Love. She can play the sophisticated, tranquil housewife a distant Jackson and well-meaning Pam (Sissy Spacek) expects of her, but before long, Grace embodies both animal and baby as well. She lunges herself through a window like a rabid creature freed from its cage, and knocks over laundry baskets and trashes the bathroom like a petulant child. When Jackson’s relentless dog barks, she barks right back with even more fervor. Her actions situate the human body as capable of high intelligence and prone to animal instinct. She has the power to take the dog out back and shoot it dead, yet the dog’s outcries – its inability to comfortably exist within its own body or suppress its woofs and growls – feel akin to Grace’s own inability to be at ease within the mold of mother and wife.

And so, it feels absolutely satisfying that Grace’s true asylum by the end of the film is the wild of the woods where red embers reign, the final scene juxtaposed with an on-the-nose frame of a cake reading “Mommy’s Home”. Ramsay strikes an impressive balance when it comes to the viewer’s relationship with Grace. She does not beg that we sympathize with her, or that we even like her. But even as Grace transforms into a spectacle on screen, the descent of her character is always rooted in depression, a very human trait. Thus, Lawrence’s vigor is grounded enough that the viewer can hope she reaches the catharsis her fragile psyche hunts.

It is reasonable to declare Die My Love as one-note. While tension between Grace and Jackson ebbs and flows and flows a bit more than it ebbs by the latter half of the film, you become aware that plot development is minimal in the grand scheme of Ramsay’s narrative goals. At the hands of a different director, I can imagine Die My Love losing itself in the hysterics of it all, devolving into something much more stale and artificial than what we ultimately get. But, as a storyteller, Ramsay has always excelled at plunging her characters into situational despair with no simple exit.

For instance, in We Need to Talk About Kevin, Eva (Tilda Swinton) is burdened by the weight of a child who diametrically opposes her in every way. His endless wailing as a baby transforms into calculations and callousness as a young adult, but holistically, Kevin’s (Ezra Miller) aptness towards making his mother’s life difficult is cyclical. Grace’s postpartum depression works in similar ways. Her disappointment with Jackson is constant. Her feelings of being misunderstood, being talked down to like a kid or a basket case, are constant. Everything is constant. Even if Die My Love is repetitive, its repetitive form only assists the flesh of the film.