I have watched 33 films over the last ten days. To ensure survival during this period, rapid mutations to my genetic makeup have enabled me to go from screening to screening, only momentarily needing to come up for air in order to refresh the ticket website 900 times and knock back a free Nespresso. The relentless festival delirium has fused together two otherwise disparate films into close association in my mind. So, bear with me while I explore the relationship between David Cronenberg’s in-competition feature The Shrouds (2024) and Charles Vidor’s 1946 film noir, Gilda.

Seventy-eight years after its presentation in competition at Cannes, Gilda has returned, fully restored from its original 35mm nitrates with 4K scanning and full audio restoration, thanks to the Cannes Classics programming. This arm of the festival, although only in its third year, has quickly become indispensable, beloved for its celebration of the history and art of cinema. The restoration of Gilda underscores the enduring significance of film noir and its influence on contemporary cinema.

The term “film noir,” coined the same year Gilda was released by critic Nino Frank, sought to define a new trend in Hollywood cinema. Defining film noir has long been debated, with uncertainty about whether it constitutes a period, genre, cycle, style, or phenomenon. Perhaps it is easier to recognize a film noir than it is to define the term. It is this ambiguous postmodern recognition that connects The Shrouds and Gilda. Considering these films in tandem is a reminder of James Naremore’s analysis that ‘film noir belongs as much to the history of ideas as much as to the history of cinema’ (More Than Night, 1998).

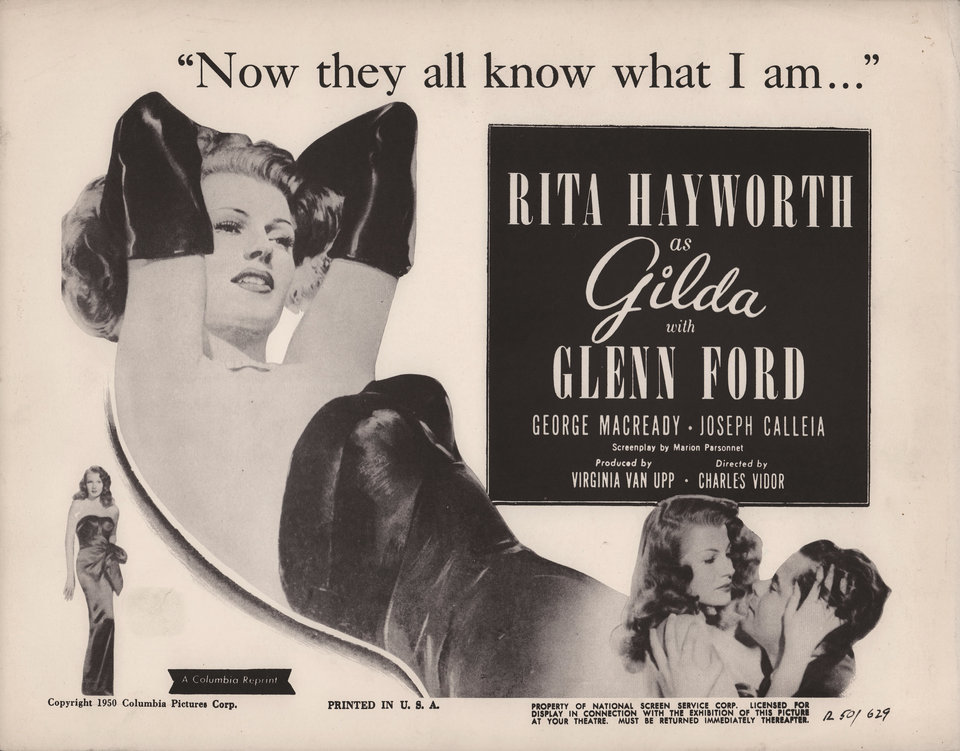

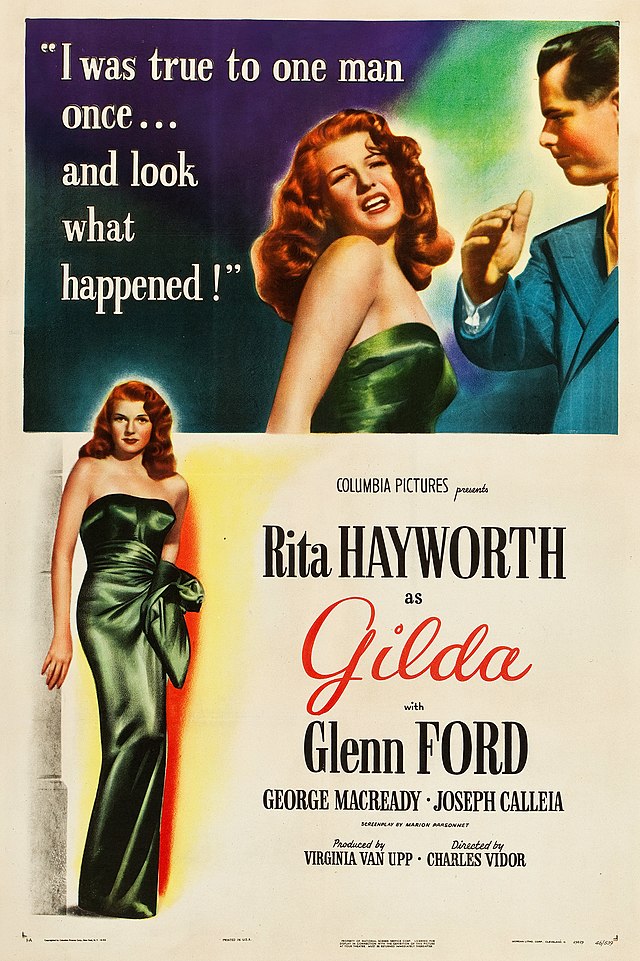

Following Naremore, film noir emerged from a European male fascination with the instinctive. The iconically eroticised character of Gilda personifies this fascination. The film’s marketing quote, “Now they all know what I am…”, reflects this desire to expose and to explore basic human instinct through film. Gilda and The Shrouds both centre around essential themes of human desire and fear. Both present eroticised violence and perform similar dances that flit between paranoid jealousy and nihilistic dissociation.

In 1946, the film noir trend was a clear rejection by young auteurs of the sentimental humanism of “museum objects” like John Ford (Frank, 1946.) The cardboard cut-out figure of the cowboy, immutable and reproducible, stands as the perfect antithesis to the murky and intangible themes and characters of the film noir. The dream-like “surrealist atmosphere of violent confusion, ambiguity or disequilibrium” defines film noir (Naremore, 1998). Both Gilda and The Shrouds operate within this style, designed to disorient the spectator. Anne Helen Petersen aptly describes Gilda‘s dreamlike quality: “When you see [Hayworth] onscreen, it seems like everyone else is just sleepwalking” (2011). Applying this idea to Cronenberg’s latest film, it seems that every character in The Shrouds is sleepwalking their way through, physically stiff and endlessly repeating dialogue.

Whilst psychological bearings and guideposts disappear in Gilda, the audience maintains a beacon amongst the discontinuity in the form of Rita Hayworth’s unforgettable performance. While Gilda offers a beacon in Rita Hayworth’s unforgettable performance amidst its discontinuity, The Shrouds denies the audience any such focal point, offering instead a pure exploitation of incoherence that exhausts the spectator and the noir formula. Gilda’s ending is perhaps the greatest moment of incoherence, as the music swells and Johnny and Gilda walk off arm in arm together to return home. Can a film noir have a happy ending? This sparked debate with a friend as we left the screening. To me there is no happy ending for Gilda. She is trapped once again in this abusive and exploitative relationship, with no escape in sight. I recognised a similarly confusing and tormented ending in The Shrouds as Karsh and Soo-Min fly off together in a private jet. However, their ironic and hopeless romantic escape ultimately lacks impact. The film ends flatly, a prisoner to its own dispassionate incoherence.

Both films, in true noir fashion, are existential allegories of the white male condition. The Shrouds and Gilda present female characters in eroticised, mutilated, or alien forms, a trope I term “the mutant woman,” borrowed from Cronenberg’s 1988 film Dead Ringers. Derived from the Latin verb mutare, meaning to change or alter, the term “mutant” helps us understand how the female figure is contorted to reflect the fears and fantasies of the white male auteur.

In The Shrouds, Diane Kruger multi-roles as Becca (Karsh’s late wife), Terry (his sister-in-law), and Hunny (his AI assistant). All exist solely within Karsh’s existential fantasies, and their portrayal by the same actor only emphasises the two-dimensionality of these characters. The image of Becca’s naked body, amputated and covered in lesions, recurs throughout the film, worsening in its condition on each reappearance. In a disturbing sequence, Hunny even takes on the form of Becca’s mutilated body, in between shapeshifting as a koala bear and an even freakier quasi-human assistant.

Gilda too is “mutant” in certain ways. Gilda is connected to the mythic and supernatural through her association with the femme fatale paragon ‘Mame’, through the song she performs twice in the film, ‘Put the Blame on Mame.’ The song is about a woman being blamed for cataclysmic disasters in American history such as The Great Chicago Fire of 1871, the Great Blizzard of 1888, and the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, all on account of her promiscuity. In addition to this, the camera, lighting and costuming all also work together to present Gilda as bisected and disembodied, as Zoe Kurland explains:

“She is framed constantly by men in dark suits who flank her, stand in front of her, or block her from the light. In one scene, Gilda lies on a bed face down, rolling in and out of sharp light panes, partaking in her own bisection. She is never fully illuminated; she turns her head and hair into the light, but we lose her body behind her husband’s silhouette. These isolated features become synecdoches for Gilda, signifying her body as whole without ever completely presenting it.” (2020)

Gilda and The Shrouds use the female body, eroticised and mutilated, as sites to explore that which patriarchal society fears most. Clearly, both films are driven by the theme of male anxiety over female infidelity. Karsh’s paranoia over his late wife’s alleged affair with her doctor accelerates the film’s unfolding delirium. And, the tagline found on posters for Gilda, “I was true to one man once … and look what happened …”, makes this theme evident without one even having to have watched the film.

Greater, societal, fears are also mapped onto the female body through both of these films. It is fascinating that in 1946, the United States conducted atomic bomb tests at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands, naming the first bomb “Gilda” and plastering an image of Hayworth onto the bomb itself. The shadow of Hollywood, in its eroticisation of violence through the female, continues to map itself onto that which society fears the most. Cronenberg stays true to the essence of noir by using the mutant woman to establish the film as part of an “antigenre that reveals the dark side of savage capitalism” (Naremore, 1998.) Becca, shrouded in body scanning technology and cloned as an avatar in Karsh’s phone, is a symbol of perhaps our greatest fear as a society today: the rapid advancement of artificial intelligence.

The exploration of The Shrouds and Gilda reveals film noir’s enduring nature as a reflection of societal anxieties and existential dilemmas. Both films use the “mutant woman” to probe patriarchal fears, showing how these themes have evolved over the decades. Gilda benefited from Rita Hayworth’s powerful influence and the involvement of female producers like Virginia Van Upp. Van Upp, a “gal producer” in 1940s and 1950s Hollywood, helped cultivate a wider audience for film noir, appealing to women’s appetite for criminality and violence (Shelley Stamp, 2020.) Considering Gilda‘s production context, The Shrouds, made by an overwhelmingly male team in 2024, exploits the concept of the “mutant woman” without offering adequate complexity or empowerment. While Gilda uses noir style to create a lasting narrative with memorable performances, The Shrouds falls into disjointed storytelling and incoherence, undermining its potential impact. The Shrouds not only exhausts the noir formula but also fails in its representation of female characters, highlighting the stark contrast in handling similar themes across different eras.

The historical and thematic connections between these films underscore Naremore’s assertion that film noir belongs as much to the history of ideas as to the history of cinema. Ultimately, noir is part of a discourse, evolving through arguments and readings. Gilda and The Shrouds exemplify this ongoing dialogue, showing how the genre adapts to express prevailing fears and fantasies.

Nespresso, anyone?